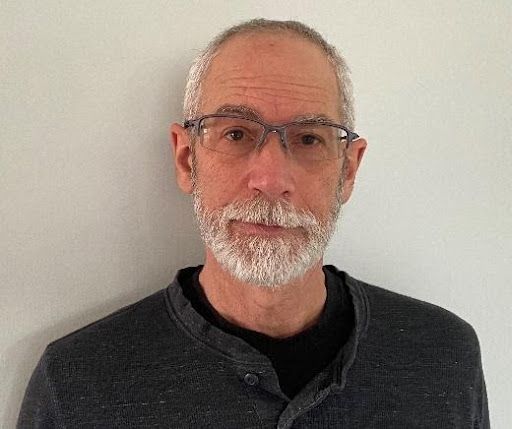

Part One of an Article by Ed Levine, (NOAA, Retired) Neptune, NJ

Introduction

The author has served over 32 years with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) first in the role of Scientific Support Coordinator (SSC) for 28 years and then as a supervisor of SSCs for five years. During this period, he participation in hundreds of actual emergency response events and exercises. He had numerous opportunities to witness both effective and not-so-effective methods of communicating, within a command post situation with other responders and incident command staff, and externally with the general public and media. The effective delivery of a message is greatly affected by circumstances under which youare operating, with whom you are talking, the information or message you are conveying, and the situation surrounding the event. Over many years, the author has gained practical experience through a variety of learning opportunities including professional development programs and on-the-job. His insights on effective communications are provided in this paper to show how messages can be delivered effectively, heard clearly and understood. Practical “tips,” best practices, anecdotes, and concrete examples will be shared to help ensure your message is heard and understood. The author provides examples drawn from actual incidents including the Deepwater Horizon, MT Heibi Spirit, TS Athos I, as well as exercises including PREPs, EcoCanal, and SONS. In addition to these incidents, exercises and drills, the author has continued to expand his knowledge through classes presented by leading subject matter experts involved with the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science, National Academy of Science, US Coast Guard, and NOAA.

The inspiration for this paper stems from the professional need to communicate science to emergency response staff, command and stakeholders, and the personal observations of how this can go surprisingly wrong or right. Sometimes it is a fluke or coincidence that can cause a situation to go from good to bad, or vice versa. Most of the time, it is accounted for in preparation. Preparation includes understanding your subject matter, knowing subject matter experts (SMEs) to consult with, making connections with your audience – be they the unified command or the general public, understanding the level and depth of information that needs to be passed, and remaining calm.

In total, through 28 years as a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Scientific Support Coordinator (SSC) plus additional five years as a Response Operations Supervisor (managing the SSC program from Maine to Louisiana), the author was the lead SSC for over 250 responses, and participated in numerous drills and exercises. The types of oil spills attended range from minor oil leaks from home heating oil tanks, to fishing vessels aground, to large oil tanker spills, to the mega Deepwater Horizon and Exxon Valdez spills. Additionally, our science support covers a host of other possible catastrophes. From biological contamination, radiation, chemical releases and train derailments, to terrorism attacks (World Trade Center), whale carcasses, floatable garbage events, sewage releases, marine debris events, medical wastes, law enforcement activities, and natural disasters such as hurricanes and flooding. Each incident required a different knowledge set concerning the data analyzed and information shared.

The manner in which the information was delivered was customized to the audience. Some examples of the different audiences would include: United States Coast Guard (USCG) – from enlisted petty officers in the field to captains in the command post, up to admirals and the Commandant – industry responsible parties, state agencies representatives, politicians, lawyers, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), the media, and the general public.

In the Boston Globe Opinion section (McIntyre, 2019) makes the case that “In graduate school, scientists are trained to become expert researchers, but almost none are schooled in effective public communication. Neither are scientists customarily asked to reflect on the logical or methodological roots of their disciplines. As a consequence, some come quite close to buying into a fairly unsophisticated view called “naive realism,” which holds that science simply discovers the truth. When called on to defend their results, some therefore seem tempted to present their findings as fact and seem shocked when an audience of doubters doesn’t believe them. But you don’t convince someone who doesn’t believe in evidence by presenting them with more evidence. You do so by helping them to improve their reasoning.” This is clearly the goal of a science advisor, to ensure the recipient of the data understands the value of the information presented and correctly interprets it to make the appropriate decisions.

DISCUSSION

In a report after a 2019 workshop held by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (AAAS), Colwell & Machlis, 2019, discuss the need for science communications during crisis situations and identify areas for improvement. Of the five recent crises referenced in the report (the World Trade Center attack, Deepwater Horizon oil spill, Super Storm Sandy, Oso Landslide, and Zika virus outbreak) the author was the science officer for the US Coast Guard for the first three. Colwell & Machlis define science during crises to include conducting scientific research and analyzing data, as well as organizing staff, communicating, and archiving scientific and technical resources during the crisis event. Crisis events are most often acute disruptions and place-specific, with consequences for both people and the environment.

Colwell & Machlis further go on to identify science during crisis as requiring the engagement of scientists and engineers across a broad range of disciplines, including emergency managers, resource managers, policy-makers, business owners, and the public. Because crises impact people and infrastructure and/or environmental assets of societal value, science during crisis is necessarily human-centric. Science during crises helps guide decision-making, from search and rescue operations and environmental remediation plans to health monitoring and evacuation planning. Further, scientific work done in emergency response directly impacts the lives and livelihoods of survivors in a crisis-affected area.

Historically, science has played an important role in emergency response situations, and the scope of that work is broadening. The Office of Strategic Services (OSS), predecessor to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), recruited scientists and engineers to provide expertise and support intelligence efforts during World War II. More recently, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Scientific Support Coordinators have served as technical experts to support the response to oil and chemical spills in U.S. waters. Other examples include the National Weather Service (NWS) Incident Meteorologist positions, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) created Global Rapid Response Teams, the Department of the Interior’s (DOI) Strategic Sciences Group (SSG), and the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) coordination with the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to ensure scientists are on site to provide situational awareness.

It is important to remain aware of the different circumstances surrounding internal communications within the command post setting and external communications with stakeholders and the public. In the command post the SSC or other Technical Specialist (Tech Spec) is invited to be a part of the command structure, and as such is a known entity coming with credentials and history. This make the SSC a trusted individual with an unbiased focus. To external audiences, this person is an unknown quantity. There may be misconceptions since this science person is working with the Responsible Party that they may be “in bed” with and plotting against the public interest.

Trust has to be built over a very short period of time to ensure that the information is passed and understood. This is where the soft skills come into play.

Suggested recommendations from the report (Colwell & Machlis, 2019) relevant to this paper include: emergency-response and scientific communities should expand joint training and outreach/education and at the onset of a crisis, a central curated clearinghouse developed in advance should be activated to collect, disseminate, and coordinate relevant scientific information. These suggestions are all leading to the fact that it is not enough to just have the best data available, one must also know how to convey that data into understandable information.

Recommendations highlighted in the report for future research in the area of communicating science during crisis specifically mention that the delivery and presentation of scientific information during a crisis—to decision-makers, the media, and the public—can significantly affect emergency response, public safety, and restoration activities.

Key questions to address include:

1. What visualization techniques and methods of delivery or presentation are best-suited to communicating scientific information to different audiences?

2. What is the best way to:

a) streamline technical communications for different audiences at different times;

b) account for a variety of scientific perspectives and findings;

c) address potential ethical concerns in the communication of sensitive data; and

d) avoid information overload, misinterpretation, and unnecessary confusion?

SSC TRAINING AND EXPERIENCE

Soft skills (identified at https://www.thebalancecareers.com/) are the personal attributes, personality traits, inherent social cues, and communication abilities needed for success on the job. Soft skills characterize how a person interacts in his or her relationships with others.

Unlike hard skills that are learned, soft skills are similar to emotions or insights that allow people to “read” others. These are much harder to learn, at least in a traditional classroom. They are also much harder to measure and evaluate.

Soft skills include attitude, communication, creative thinking, work ethic teamwork, networking, decision making, positivity, time management, motivation, flexibility, problem-solving, critical thinking, and conflict resolution.

Image by Kelly Miller. © The Balance 2018

https://www.thebalancecareers.com/top-soft-skills-for-customer-service-jobs-2063746

NOAA’s Emergency Response Division (ERD) spends extensive time and effort training SSCs on “hard” science subjects such as chemistry, biology, physical processes, and health and safety. To provide needed technical services, SSCs must also develop “soft” skills to enable successful interaction with clients and the response community. The soft skills SSCs need are listed below, but this list certainly does not include all the soft skills and abilities SSCs need to bring to bear during responses, planning sessions, meetings, and their many other activities.

“Soft” skills and abilities of SSCs include:

| Communicating | Coordinating | Negotiating | Organizing | Humor |

| Cooperation | Planning | Questioning | Leading | Confidant |

| Trainer | Writing | Demonstrating | Advocating | Initiative |

| Mentoring | Compassion | Navigating | Disseminating | Advising |

| Interpretation | Correlation | Anticipating | Institutional knowledge | |

| “Watchdog” | Listening | Empathetic | Teaching | Problem-solving |