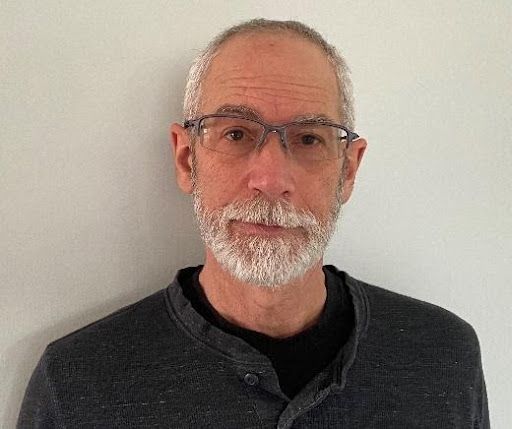

Part Two of an Article by Ed Levine, (NOAA, Retired) Neptune, NJ

FUTURE IMPLICATIONS

In an attempt to broaden the use of a science advisor to different disaster events, several Coast Guard officers and NOAA SSC described and proposed to FEMA the concept of a multi-hazard response science advisor based off the NOAA SSC role. FEMA adopted this concept and added the Science and Technology Advisor (STA) position onto the Incident Command staff in the September 2017 FEMA-509-v20170717 National Incident Management System (NIMS). Under the resource typing definition for the National Qualification System Emergency Management the STA “provides advice and informs decision-making for all science and technology-related incident activities” including:

1. Monitors incident operations and provides scientific and technical advice on matters relating to the integration of science and technology into incident response efforts

2. Enhances safety, assists in incident action planning, and informs decision-making for all science and technology-related incident activities

3. Consults with subject matter experts in the scientific and technological communities to gather information, serve as a liaison, and make recommendations to the incident command, Unified Command, or center director

4. Maintains an extensive network throughout the scientific community and draws from this resource as necessary to help inform incident operations

5. Ensures proper information management of scientific data acquired during incident operations and field testing

6. Disseminates technical information and training to all response personnel who may need special knowledge relating to incident planning and response activities

It is further suggested here, that the STA position also include skills and training in communications and outreach (as listed above for the SSCs), for communications both internal to the ICS and externally to other stakeholders.

LIFE LESSONS LEARNED THROUGH THE YEARS

Know Your Facts:

• People want accurate information about what happened and how that event might affect them. (Barton. 2001)

• Information should be consistent.

• Because of the time pressure in a crisis there is a risk of inaccurate information, if mistakes are made, they should be corrected ASAP.

• The philosophy of speaking with one voice in a crisis is a way to maintain accuracy.

• Speaking with “one voice” does not mean only one person speaks for the organization. It refers to using an agreed upon set of facts to disseminate information.

Talk About What You Know:

• Let the audience know your credentials and reason for talking with them – why they should believe you.

• This includes life experiences as well as academic degrees. The life experiences may even outweigh academic learnings.

Know What You Don’t Know (as much as you can):

• It is perfectly reasonable to respond to a question by stating that you do not know the answer and will attempt to get that information at a later time.

• My favorite quote from a colleague, Dr. Jerry Galt, is “We reserve the right to be smarter, later.” This infers learning as new data becomes available and adjusting hypotheses and potential outcomes to fit the new information.

• Deliver all information promised to stakeholders as soon as that information is known.

• A quote, from Dr. Jacqui Michel, pertaining to the vagaries of responding to an oil spill is “I’ve never been to the same spill twice.” The interpretation of this is that something is always different, and just because you were at a similar incident, does not ensure that the new incident will have the same outcome.

Know Your Audience:

• Set the appropriate tone and voice for your message. This includes your appearance.

• Present information clearly by avoiding jargon or technical terms.

• Use analogies as appropriate.

• Lack of clarity makes people think the organization is purposefully being confusing in order to hide something.

Be Empathetic:

• Show your humanity. Allow people to see you are human as well as a representative for the response.

• Connect with the people you are talking with (not to).

“Developing empathy and learning to recognize what the other person is thinking are both essential to good communications. Communications does not take place because you tell somebody something. It takes place when you observe them closely and track their ability to follow you. The responsibility really belongs to the person speaking, not the person listening.” – Alan Alda (Alda. 2017)

Use Your Heart and Mind:

• Remember you are dealing with a stressful situation. Try to not make it any more stressful.

• Be sympathetic to the situation surrounding the incident.

• Remain calm.

Social Awareness:

• Be aware of others inner state (empathy).

• Grasp their feelings and thoughts (Theory of Mind).

• Recognize complicated social situations (understanding).

Instead of But Use And Yes – make it positive:

• “And yes” helps expand the conversation.

• “But” narrows a conversation and appears to contradict.

Tell a Story:

• Stories are powerful ways to connect to people.

• Everyone loves a good story. Take your message and see how you can craft it into a story with a beginning, middle and end. Design a plot – good versus evil, a twist they do not see coming, overcoming adversity, etc.

• Analogies may be helpful if they are understandable and relevant.

Start with the End – Why are you here – your positive goal:

• Introduce up-front the purpose and message synopsis.

• Let people know what to expect.

Avoid:

• “I know what I am talking about and that ends the discussion.”

• “You won’t understand.”

• “Trust me.”

REAL-WORLD CASE LESSONS LEARNED

The following incidents have been real-world case used here to illustrate some of the items enumerated above:

– Paulsboro, NJ vinyl chloride incident (2012) – Know Your Audience: A Town Hall meeting was initially set up to inform the public concerning the current state of the response. It was to be a college-fair type of event. The public address system failed and in order to be heard one of the NJ representatives began shouting at the audience. The crowd began shouting back and the moderator began losing control of the situation. Ultimately, a USCG Public Affairs Specialist took the podium and organized people to begin going to the appropriate booths to get their specific questions answered. This refocused the event back on track. Otherwise it was heading to be a disastrous mob situation.

– DWH (2010) – Tell a Story: During a briefing with Adm. Thad Allen (USCG, retired) he asked about the status of the dispersant operations that were occurring for many weeks. To best describe the situation, the author used a Star Trek analogy stating “We are in uncharted territory.” He understood that we had exceeded any previous experiences we had using this quantity of dispersants and we were learning as we went along.

– DWH (2010) – Use Your Heart and Mind: During a Town Hall meeting set up to discuss dispersant operations with the public a specific connection with a couple stood out. They were very concerned about the possible effects the dispersant would have on the water quality and how it would affect their children. The husband was wearing a Harley Davison tee-shirt. The author connected to him first as another Harley owner, then found out their specific concerns and was able to alleviate them by giving the parents the facts about where the dispersants were being applied, the ongoing monitoring, and the safety measures in place.

– DWH (2010) – Be Empathetic: The USCG Incident Commander attended a Town Hall meeting to discuss the response efforts. His opening statements talked personally about his dedication to the public to make the response as effective as possible. He stated he was missing his son’s birthday that evening to be here working and talking to the audience. As most of the audience were parents this had a direct impact on them.

– DWH (2010) – Talk About What You Know: In an early press interview with the media, to help set expectations, the author stated what he knew from previous response experience and the movement of oil on the water, that the oil will eventually come ashore. This was the first time the subject was mentioned. Within the next couple of weeks, the oil came ashore.

– MT Rio Puelo “Lemon” incident (2004) – Know Your Facts. Know What You Do Not Know: During this response there were many gaps in the knowledge of what the actual threat was. The SSC had to translate a complex bioterrorism threat from the science group to decision-makers with a great deal of uncertainty. As it turned out, the whole incident was a hoax, but it turned out to be a great learning opportunity and exercise for the response community.

– TV Athos I (2004) – Start With The End, Managing Expectation: After the Salem Nuclear Power Plant shutdown due to oil in its intakes, the USCG Incident Commander told me “It’s up to you to tell them when to restart the nuclear reactor.” After sleeping on this directive, the next morning, the author told the Captain that it was my job to provide the information to the plant operators and their decision when it was safe to restart the power plant.

– TV Hebei Spirit (2007) – Know Your Facts: While discussing the effectiveness of dispersant operations, the Korean Coast Guard commander asked “How do we know if the dispersants are working?” My rhetorical reply was “Did you look?” Not being facetious, the author discussed how to monitor for dispersant effectiveness both in the water with instrumentation and visually from the air.

– San Jacinto Spill (1994) – Know Your Audience: The Unified Command attended a town hall meeting with local residents. The degree of outrage by the attendees was not anticipated. There was a great deal of hostility and anger about how the incident was affecting property owners. The Unified Command did not have the confidence of the public nor were they able to overcome the animosity present. This turned into a terrible Town Hall event due to lack of preparation.

CONCLUSIONS

Oil spills, are by definition, chaotic events. Conditions often change rapidly as the oil moves through the environment and is subject to currents, waves, weather and whatever is in its path. When time and resources are limited, responders need sound science to make informed decisions to minimize impacts to natural resources, and the communities and economies that depend on them.

NOAA scientists must also quickly help determine what the properties of the oil are, where the oil is going, what organisms and environments are in its path, and what can be done to help mitigate the impacts to minimize exposure and injury to natural resources. NOAA experts need to be able to communicate their facts, discuss the uncertainties and discrepancies – as there may be more than one way to interpret data, and enable decision-makers within a command post to understand and move forward as time is usually of the essence in these incidents. Additionally, the data that decisions have been based on need to be made available to the public and media in understandable ways, which will by necessity be different than communicating within the command post.

While the gaining of scientific knowledge can be obtained through books, schooling and study, the ability to pass on that knowledge is another skill altogether. The ability to communicate takes a different set of skills, practice, feedback, and overcoming hurdles. There have been numerous studies and observational instances of leading experts in their field of studies not being capable of fluently explaining the content, context, and implications of their work to people not in their field of expertise. The implications of this are very different when science communications hinges on quick decision-making when 100% of the facts are not in. The essence of this paper is to demonstrate the need for “soft skills” to coherently and sympathetically communicate “hard science” facts and figures to people without advanced degrees in hard science.

REFERENCES

Alda, A. 2017. If I Understood You, Would I Have This Look On My Face? My Adventures in the Art and Science of Relating and Communicating. Mayflower Publications, Inc. 213pp.

Barton, L. Crisis in Organizations II. Cincinnati: South-Western, 2001. 287 pages.

Colwell, R. & G. Machlis. Science During Crisis: Best Practices, Research Needs, and Policy Priorities.

Cambridge, MA. American Academy of Arts and Sciences. 2019.

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). National Incident Management System (NIMS). Third Edition. October 2017. https://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/1508151197225-ced8c60378c3936adb92c1a3ee6f6564/FINAL_NIMS_2017.pdf

McIntyre, L. What’s so special about science? Boston Globe Opinion. Updated May 6, 2019

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Scientific Support Coordinator Training Guidebook. 2019.

The BalanceCareers. 2019. https://www.thebalancecareers.com/